Few trajectories in the recent history of Brazilian museums reveal such a rare combination of intellectual rigor, curatorial sensitivity and institutional dedication to Zuzana Trepková Paternostro. Born in Central Europe and graduated in Art History and Theory, Zuzana built in Brazil — more precisely in Museu Nacional de Belas Artes — a career marked by in-depth research, for the silent discovery of works and the training of generations of researchers.

Over almost four decades dedicated to the MNBA, served as curator of Foreign Painting, researching, assigning, restoring and exhibiting around a thousand works, especially from the European tradition, always guided by a refined technical eye and a historical understanding that goes beyond fads and hasty readings. His work helped to reveal to the Brazilian public the richness of a collection that, and often, remains better known outside the country than inside it.

Recently, Zuzana brought this journey together in a restricted circulation book, aimed at specialists, in which it synthesizes decades of research, curation and commitment to cultural heritage. More than a career balance, the publication reflects an intellectual stance in permanent movement — averse to stagnation, open to critical review and deeply connected to museum work.

In this interview with WebSite Artworks, Zuzana Trepková Paternostro talks about cultural displacement, training, search, the “mysteries” of artistic attribution, the role of the curator in the face of the market and counterfeits, the structural challenges of public museums in Brazil and, especially, about art as an essential element of the human experience. A rare testimony from someone who made art not just a profession, but a way of existing.

Trajectory, Identity and Cultural Displacement

You were born and trained in Central Europe, but he built his professional life in Brazil. At what point did you realize that Rio de Janeiro had become, in fact, your place in the world?

It wasn't Rio de Janeiro. So that now, activate, Brazil, as a whole. This country has always occupied one of the central places of my curiosity, since adolescence. Coincidentally, I met an engineer from Rio who I married and went to live with him in Rio. My calling for adventure, including professionally speaking, took me to this city. I changed the job I had been in for five years, at the National Gallery of Fine Arts, the main one in my capital, Bratislava, by the National Museum of Fine Arts.

In interviews, you comment that, at first, I was surprised by the open and smiling way of Brazilians. Eventually, what else did you learn – humanly and culturally – living in Brazil for more than five decades?

I learned to be more tolerant. And it wasn't easy: It took a long time to cool down my somewhat impetuous reactions.. I still exercised my creativity better and discovered a way to take life more lightly.

Looking today at your trajectory between different cultural contexts, How did your academic training and professional experience in Brazil complement each other throughout your career??

It was a symbiosis, a very happy synthesis, because I managed to control my anxiety to the point of waiting for the right moment for everything I intended and dreamed of doing. In addition to expressing my ‘truths’ with the necessary conviction and tranquility.

The MNBA and Curatorial Work

The lady dedicated 39 years of his life to the National Museum of Fine Arts. What the MNBA represented for your training as a researcher and curator – and what he believes he left as a lasting contribution to the institution?

Be accepted by the National Museum of Fine Arts, and then manage to stay in it for decades, It was the best thing that happened in my professional life. After all, I joined a national institution, even though I'm quite young. At the same time, I took my cultural baggage, knowledge of foreign art, basically European, that he had from an early age. Being from Central Europe, I embraced all aspects and capillaries of Europe as a whole. I believe that this book of mine summarizes everything I have worked on over the decades. I know I contributed as a curator, in exhibitions that featured foreign art, basically European, to greater national knowledge, linking it to a proper understanding and knowledge, just as I did with Brazilian art itself.

His work was deeply linked to the MNBA's collection of foreign paintings. In your vision, This collection is still little known by the general Brazilian public?

With deep regret, I assert that, Unfortunately, the scope of the collection and exhibition capacity of this institution does not have the ideal scope. For several reasons. Mainly, due to the necessary subsidies for the dissemination that Brazil and the Brazilian people deserve. I regret that the Brazilian public, regardless of age group and more depending on social class, have more opportunities to get to know, before the collection itself, foreign works on the spot. It's a cultural issue. Brazilian goes to Paris and visits the Louvre. Go to Madrid and enter the Prado. Already in Brazil, Would you rather see Christ the Redeemer or the Sugar Loaf Cable Car?, instead of visiting the National Museum of Fine Arts. I came to the conclusion that Brazil is a country with an environmental vocation. The Brazilian, in general, likes the outdoors, and this is understandable and commendable, because he is so connected to nature. Even so, when traveling abroad, visits the main closed areas with extreme curiosity.

Throughout his career, you supervised research, assignments, restorations and exhibitions of around a thousand works. There is a “look” which develops over time to identify hidden stories in paintings?

Exists. And I had the privilege of acquiring this perspective at a polytechnic school that I embraced even before graduating in History and as a critic of Works of Art.. It was exclusive to young talents and admission was throughout Slovakia. There I was able to learn and practice techniques such as, fresco, esgrafito and fresh dry, among others. To this perspective was added my training at the School of Restorations of Works of Art, which I studied at UFRJ with professor Edson Motta, which allowed me to see what current curators don't even have time to delve into in depth. Such as technical knowledge and analyzes of supports and pigments, which are absolutely necessary to arrive at the research of details that bring the work closer to its creator. That said, as I am a specialist in works of art from the past, I became aware of Modern Art, but I don't venture into Contemporary Art. I am aware of my limits.

Search, Attribution and “Mysteries” of art

In your interview with Pravda, You compare many artistic investigations to detective stories. What fascinated you most about this process of discovering authorship?, era or later interventions in a work?

The largest portion of the foreign painting collection I researched was European Art. A high percentage concerned paintings from the 18th and 19th centuries. The process of discovery or getting closer to some author or region, or even the century belonging, starts by examining the screen, that is, the support material. As well as knowledge of the pigments used. That said, What fascinated me most about this process was the challenge of finding out where it was made, by whom and at what time, and then present it to the public.

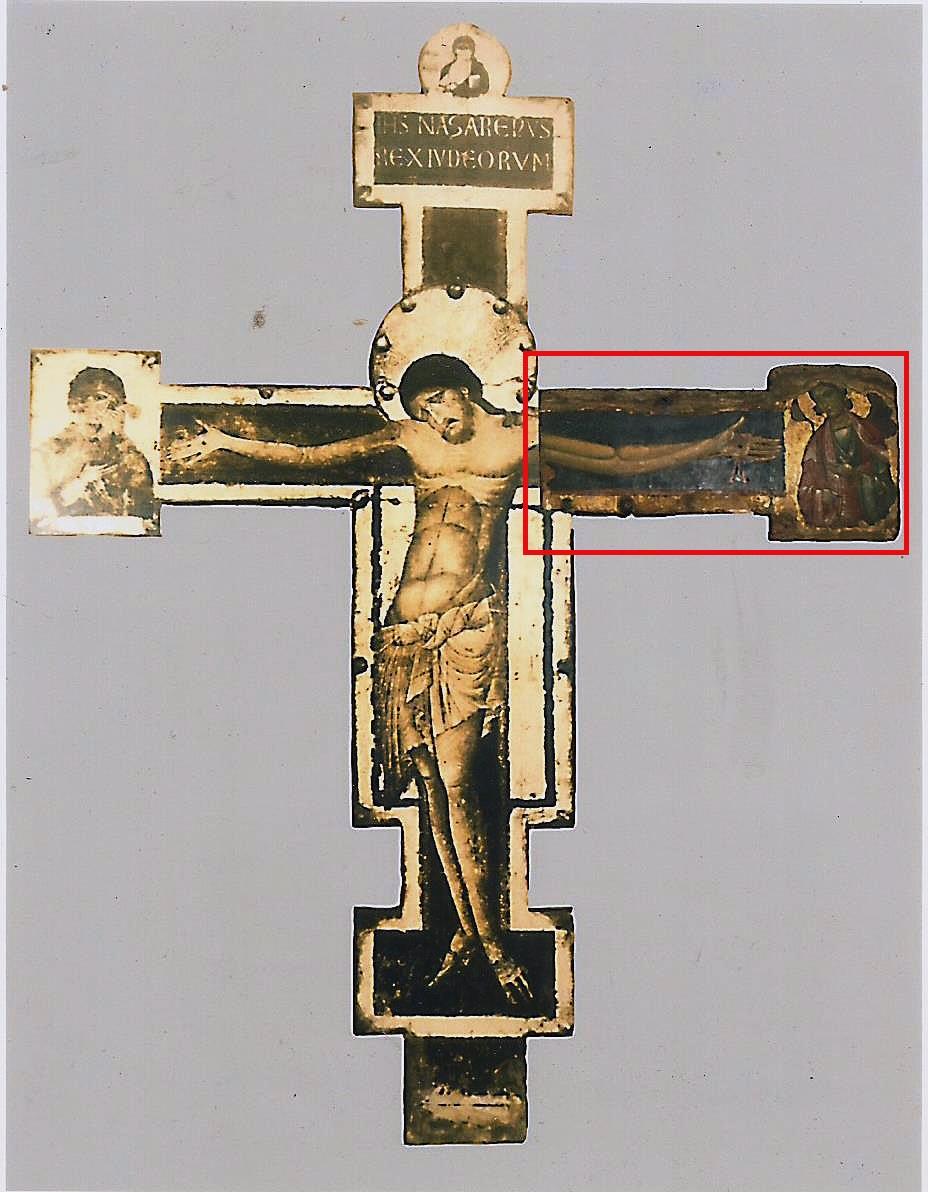

Could you tell us a little more about the case of the 13th century processional cross that was displayed in Italy? – and what this experience meant for your career?

When journalist and businessman Assis Chateaubriand invited Pietro Maria Bardi (1900-1999) to come from Italy to help form the São Paulo Museum of Art, the Masp, in 1946, first Bardi arrived in Rio de Janeiro. To honor your arrival, the National Museum of Fine Arts organized an exhibition of works with religious content. on that occasion, Bardi presented the institution as a gift by donating a fragment he had brought to the museum. It was the fragment that is an arm of a processional cross that, at the time, was attributed to one of the artists members of the Pisano family, from Pisa, Italy. By way of antiquity, it was a fragment of painting prior to the discovery of oil painting and made using the tempera technique, one of the medieval techniques applied to wooden support . When I was already working at the Museum, I took this fragment to a large exhibition in Pisa, which allowed me to participate in a conference where I witnessed a true duel of knowledge between two experts, including an Austrian, both competing to determine the author of the work. Coube ao Italian Lorenzo Carletti (1969) confirm that it dates from the 13th century, therefore, It is the oldest piece in the National Museum of Fine Arts. Carletti defined its author as someone who was not from Pisa. Was, activate, a master, but did not sign the works. He made crosses in his workshop, as usual in the Middle Ages, in the city of Calci, in the Tuscany region, a few kilometers from neighboring Pisa. Its identification and location were revealed based on an ornament repeated in all the works produced in its ‘bottega’. Even without signing, That work has immense artistic and even more historical importance, obviously. Out of curiosity: this fragment is just one of the arms of the cross while its entirety is found in the episcopal museum in Avignon, France. The Italian request to study exhibiting the Brazilian work, leaving the rest of the 'French' work geographically more accessible, represents a prestige., sideways.

How do you see the role of the curator and art historian in protecting cultural heritage from the market?, of falsifications and misreadings?

At my point of view, he needs to have academic training. 'Cause all your intuition, all secular experience, adds to that. This is how he learns discipline and the proper use of tools and methods. If you just focus on quotes from sociologists or philosophers, will leave something to be desired. For the most correct diagnosis, with regard to identifying works, alignment between technical knowledge and practice is necessary. Being together, look closely, is as or more valuable than theory. Without this care, suddenly you find yourself in front of a well-made copy, but not something original.

The Book and the Intellectual Legacy

Your book “Promoting the National Museum of Fine Arts for over Five Decades” It is not a book aimed at the general public, more to specialists. Even so, What type of reader do you hope will approach this work??

As it is a very limited edition, This book is aimed at future museologists and historians who will work in art institutions. It's for experts. To, Let's say, the future ‘Zuzanas’ to come.

By bringing together decades of work into a single volume, Was there any new discovery or reflection on one’s own trajectory??

Sign up to receive Event News

and the Universe of Arts first!

This is a permanent process. Increasingly, research instruments and pigment analysis present us with new paths. Nobody, in my area, can afford to stagnate. Many times, you need to return to an assignment that has already been made, because so-called discoveries are always subject to new interpretations.

Do you consider this book to be a point at the end of a cycle or another link within an intellectual journey that continues?

Particularly, I would like to continue working in this area. I have a genuine interest in Art; she is vital to my existence. It may even be much more important to me than to others, but I always face new challenges. Who retires, body and mind atrophy. I feel healthy enough to continue expanding my legacy.

Art, Training and New Generations

Throughout his career, You guided generations of researchers. What changed – and what remains essential – in the training of art historians today?

They have the basics, essential to starting your career. You have to like your mission, which is often confused with your life purpose. I see current historians with good eyes and wish them success. So that now, currently, there is a lot of visual information, what I even call ‘visual pollution’, and this can confuse them or take their focus away. I hope that you will stop at a selection of information that is impossible to leave aside. And may this part guide your research.. Focus is needed. They have to have dynamism, always starting from the micro to the macro.

What advice would you give to young researchers and curators who want to work with historical collections and public museums in Brazil??

I can't give advice, because I myself need advice and opinions. I am not and will never be complete: I'm always in training. I just have the impression that we need to couple anthropocentrism to the environment, by nature. We are exploring our dimension of land and nature, and that is part of being human. Man is inseparable from his environment. no more, for those who dream of working with historical collections in public museums, especially not Brazil, they must have a lot of patience, because bureaucracies, the obstacles, they are huge. Among all the faces of Culture, as Literature and Music, to name just two, Fine Arts are the most difficult, in the sense of investment. For being less popular, the least widespread and the most restricted to a select public. The museum is one of the most expensive elements of culture to maintain: requires research, technical reserve, assembly, Security, air conditioning control, fire prevention and a controlled physical space. If it was little, generates less revenue than a music festival. Fine arts and museums cost more than any other investment in Culture.

Do you believe that Brazil adequately values its museums and professionals in the field of cultural heritage?

To the extent that they do not achieve the adequate response and are not part of the main priorities of governments, are not valued correctly precisely because they do not generate results and also have a restricted audience. Within this scenario, I even think their valuation is appropriate. However, a career plan could be made, what is going on in Congress, since, Postgraduate studies for civil servants are not included in the current culture career, what has been happening for decades in the area of Science and Technology, just to give an example. In the background, There isn't even a faculty for that. Whereas architects have postgraduate degrees and everything else. Art historian does not exist in terms of career framework. When I arrived, There wasn’t even a faculty for art historians.. Today there is, almost thirty years ago. I hope this changes too.

Personal View and Final Reflection

Is there any work, artist or artistic period that still awakens in you the same curiosity as at the beginning of your career?

For me, All works are worthy of appreciation and greater attention, but among the research I continue to do around the world, I found an artist who was a portraitist of the Imperial family in Brazil, one of the most successful of his time, even though I only spent four years here. He is from the Czech Republic and was invited to visit the country through Araújo Porto Alegre (1806-1879), an art historian and critic. Both met in Lisbon. I can say that he was the most productive of the portrait artists we had. There are works in Rio, in Florianópolis, in Portugal. He was a portraitist of the European aristocracy and worked at the courts of Naples, as well as in Germany and Austria. As an adventurer, came to Brazil on his own and applied his specialty here, the portraiture, but he also made landscapes, as a canvas of the coastal city of Cabo Frio. This painting is now in Germany. His name is Ferdinand Krumholz (1810-1878). Despite portraitist, What interests me about him are his landscapes, made voluntarily and not to order, like the portraits, your main livelihood. traveling painter, after leaving Brazil, he landed in India. I learned about the existence of these works in Bombay and almost left Shanghai for India in search of them, when I heard one was on display at the Moravian Art Gallery (Brno), in the Czech Republic.

After a life dedicated to art, research and curation, What do you consider to be the true role of art in people’s lives??

Art is what distinguishes us from the animal world. We are the only living beings that need fantasy, creation, achievement, beyond what is restricted for survival. Man's subjective and interpretative capacity is what differentiates him and personifies his desire, your veneration.

To end: If you could leave a message for future generations who will take care of museums and cultural heritage, what would it be?

It takes patience and humility. Added to this is a drive to do things and no fear of facing challenges. You also need to know how to take one step back to move three steps forward.. And, although love is a worn out word these days, beyond the money itself, you need to respect and recognize what is Art.

…